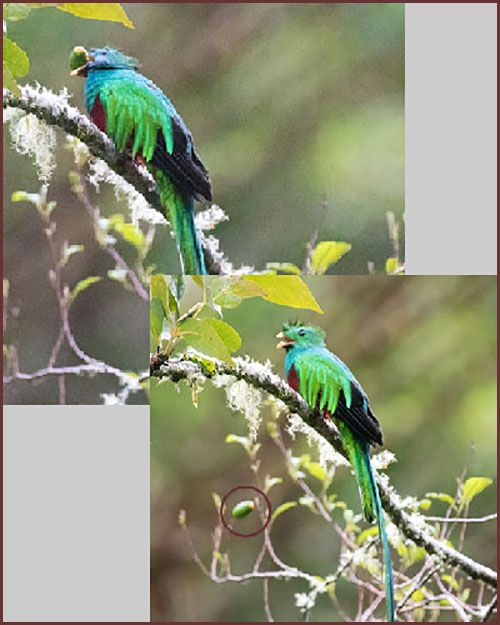

Birds of Panama, the Resplendent Quetzal, the mythical bird

The Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomacrhus mocinno) is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful birds in the Americas. As such, it has often been revered since ancient times by Mesoamerican civilizations.

Mythical, did you say mythical?

It was a sacred bird for the Aztecs, an incarnation of one of their deities, Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent. The caciques used the long tail feathers of the males to make their headdresses. For these purposes, some of these superb birds were raised in captivity.

For their part, the Mayans of Yucatan considered it the incarnation of their god Kukulkan.

Today, it is the national bird of Guatemala, which has placed it majestically on its emblem. It is also the name of the currency of this country.

Mythical too, because as my friend Christophe Henry wrote with a touch of humor on my other blog in 2010: There are two kinds of human beings, those who have seen the Quetzal, and those who have not.

This is true for ornithologists, photographers or not, who come to look for it in its distribution areas between Mexico and Panama.

For years, as a guide, I have accompanied many of its enthusiasts to my favorite spots in Panama, so that they could observe them. And, of course, a faithful admirer, I never fail to visit them on the foothills of the Barú volcano where they come every year to spend the breeding season.

The Quetzal is not a great migrant but moves according to the fruiting periods of fruit trees. Here, in Panama, from February, Quetzals move up to the foothills of certain volcanoes in the Chiriqui region, between 1200 and 1800 meters of altitude. There, they find the fruits of their favorite host trees (*1) and dead trees, still vertical, in which to dig their nests.

The period and location are therefore favorable for observations. Of course, these must be done with the utmost discretion so as not to disturb them during this delicate period.

As soon as pairs are formed, males and females take turns digging a nest by enlarging a small existing cavity in a dead tree with a decaying core. Sometimes, an old nest can be re-arranged.

On two occasions, I observed that while the nest seemed finished, the female seemed to indicate that she would prefer another one… construction would then resume in a not-too-distant dead tree.

When it is ready, the female lays 2 eggs two or three days apart. At birth, there will therefore be an elder and a younger, noticed at the feeding times.

Incubation then begins, lasting 16 to 18 days. During the day, when she goes out to feed, the male then takes over.

The rearing of the young lasts 20 to 30 days; initially, they are fed insects, then mainly seeds and fruits.

From what I have observed, a feeding routine is followed. Male and female take turns alternately to feed the chicks (approximately every ¾ hour). Arriving with a fruit in their beak, they land not far from the nest for a security inspection. The elder waits near the opening; once served, the adult returns to its observation post and then delivers a second fruit, which it has regurgitated, to the younger.

Alas, the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) notes that the population is decreasing and classifies it as “near threatened.” (*2)

Notes:

Notes:

*1- Mainly trees of the Lauraceae family. One of its favorites: Ocotea pharomachrosorum (described in 1993, its scientific name refers to that of the resplendent quetzal: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3391416

*3- IUCN classification